Prosecution for obscenity has historically been one of the best ways to ensure literary posterity. For decades, getting “banned in Boston” was a surefire way to boost sales everywhere else in the States; in the United Kingdom, 200,000 copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover sold in a single day when the uncensored version appeared. James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen: A Comedy of Justice went before a court in 1922 and became a bestseller, but today Cabell has met the fate of many “writers’ writers”: He is best remembered for being forgotten.

Though some writers go into and out of fashion, and into and out of print, every decade or so, Cabell seems to have settled into obscurity. When Lin Carter reissued several Cabell novels in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series in the sixties and seventies, his introductory remarks included the observation that some of these novels had gone forty-five years without a new edition. Since the Ballantine books have fallen out of print, most of Cabell’s works have gone without mass-market re-publication, though, since Cabell has entered the public domain, there have been print-on-demand editions. But perhaps that trial did help preserve Cabell: Jurgen has remained in print.

I’m not certain, but Jurgen may be the only fantasy novel about a pawnbroker. Though he was once a dashing young poet, a prolific lover, a habitual adventurer, and an occasional duelist, our Jurgen’s tale begins when he is middle-aged and semi-respectable “monstrous clever fellow,” with a crowded shop, a difficult wife, and little time for poetry. His brother-in-law is a grocer, his sister-in-law married a notary, and his first love—certainly not the woman he married—has grown fat and silly. Jurgen has set aside his youthful will to action, but has not quite discarded his eloquence. After a chance encounter with the devil, who is much impressed by Jurgen’s praise of his works (“it does not behoove God-fearing persons to speak with disrespect of the divinely appointed Prince of Darkness. To your further confusion, consider this monarch’s industry! day and night you may detect him toiling at the task Heaven set him. That is a thing can be said of few communicants and of no monks”) and who decides to reward this remarkable man. Soon enough, Jurgen’s wife has vanished, his youth has returned, and adventures beckon. The newly young Jurgen plays at being king, pope, and emperor; spends a night as a ghost; encounters Pan in a forest and Satan in Hell; visits Cocaigne and Cameliard; and otherwise leads an exciting life.

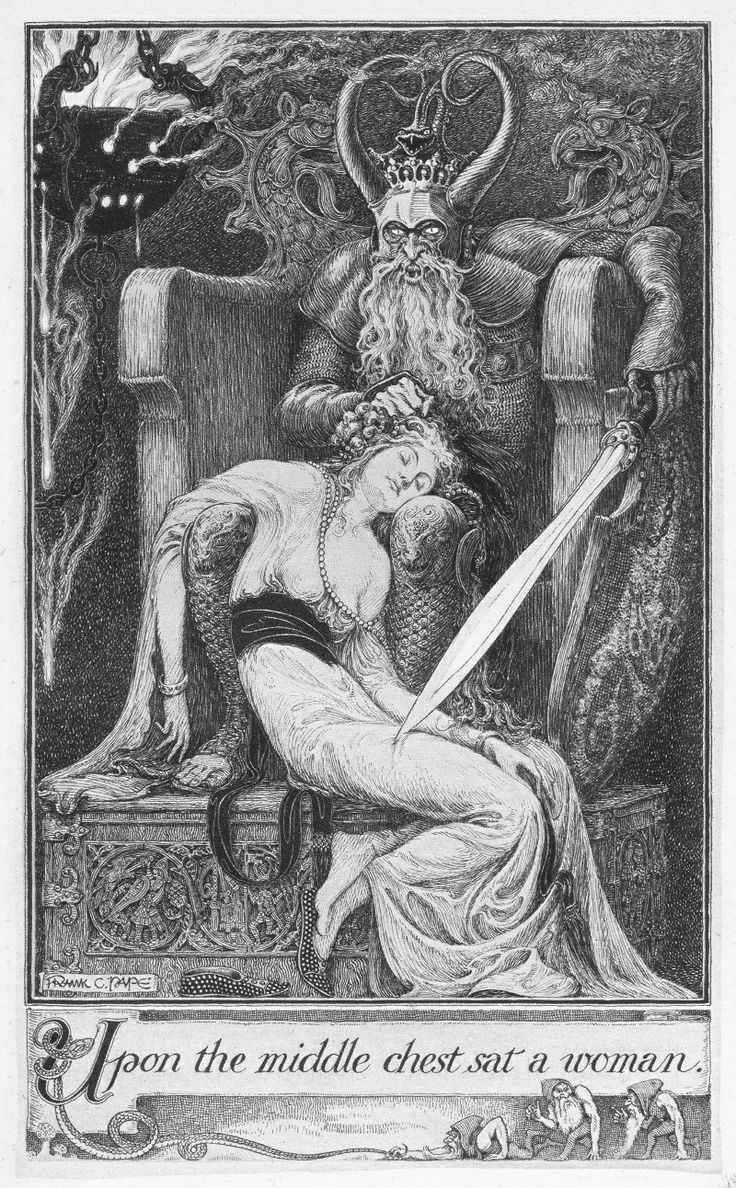

Since I opened this article with a discussion of Jurgen’s purported indecency, you may be wondering just what these obscenities consist of. Mostly they’re double-entendres; Jurgen is remarkably skilled with his lance, his sword, and his staff, and happy to introduce them to any woman he meets. So, for example:

“It is undoubtedly a very large sword,” said she: “oh, a magnificent sword, as I can perceive even in the dark. But Smoit, I repeat, is not here to measure weapons with you.

And later:

Jurgen lifted Anaïtis from the altar, and they went into the chancel and searched for the adytum. There seemed to be no doors anywhere in the chancel: but presently Jurgen found an opening screened by a pink veil. Jurgen thrust with his lance and broke this veil. He heard the sound of one brief wailing cry: it was followed by soft laughter. So Jurgen came into the adytum.

And still later:

“Why, I travel with a staff, my dear, as you perceive: and it suffices me.”

“Certainly it is large enough, in all conscience. Alas, young outlander, who call yourself a king! you carry the bludgeon of a highwayman, and I am afraid of it.”

“My staff is a twig from Yggdrasill, the tree of universal life: Thersitês gave it me, and the sap that throbs therein arises from the Undar fountain, where the grave Norns make laws for men and fix their destinies.”

Can a book be so sexually implicit that it becomes sexually explicit? In 1919—fifteen years before the publication of Tropic of Cancer and forty years before the Chatterley trial—this material could still shock many readers; today, without the context of a prudish culture, it often seems juvenile. I won’t deny that I laughed, but sometimes I wanted to roll my eyes.

I suspect that many modern readers would dismiss Jurgen as an outdated cocktail (cock-tale?) of adolescent jokes, casual sexism, artistic self-indulgence, and authorial self-importance. Even the quick summary I gave above suggests that Cabell’s attitude towards women—or perhaps I should say Woman, given the story’s allegorical bent and the apparent interchangeability of the story’s women—is unfortunate, and I cannot claim that all of the jokes land—the parody of Anthony Comstock, for example, may have passed its sell-by date. A brief passage inserted after the obscenity trial includes a scene of Jurgen haranguing the people of “Philistia” for their poor treatment of brave artists, especially Mark (Twain), Edgar (Allan Poe), and Walt (Whitman). Even if you agree with the argument, it’s a little embarrassing to see Cabell comparing himself to three acknowledged masters, all of whom have outlasted Cabell’s acclaim. (To be fair: Twain was an admirer of Cabell.) So do I conclude that Cabell’s reputation deserves its eclipse? No. As Jurgen puts it after receiving a cosmic vision of his own insignificance:

None the less, I think there is something in me which will endure. I am fettered by cowardice, I am enfeebled by disastrous memories; and I am maimed by old follies. Still, I seem to detect in myself something which is permanent and rather fine.

I concur: Whatever its shortcomings, any book so elegantly written, so consistently funny, and so confident in itself deserves admiration.

Lin Carter, another man who clearly thought Jurgen permanent and rather fine, didn’t quite manage to restore Cabell’s reputation with his Ballantine reissues, but science fiction and fantasy writers have never quite forgotten him either. Robert Heinlein’s late novel Job: A Comedy of Justice is an explicit homage to Cabell in general and Jurgen in particular. Jurgen’s love of roguery, love of love, and wry eloquence reminded me of characters in Jack Vance’s fiction; I wouldn’t be at all surprised if Vance had read Cabell.More recently, Michael Swanwick wrote a fine monograph on Cabell called “What Can Be Saved from the Wreckage?”; anyone with an interest in Cabell should consider seeking it out. I cannot say for sure if Swanwick counts Cabell as an influence, but I see something of Jurgen in some of his eloquently disreputable characters. Neil Gaiman says that Cabell’s books are personal favorites; close readers of his books will spot an occasional reference.

Jurgen, for all its swordplay and staff-work, is not frivolous. The “Comedy of Justice” is the ridiculous and ludicrous injustice of the human condition: We age and die, abandon our hopes, fail our dreams, and muck up those few second chances we’re lucky enough to receive. Jurgen, restored to his original life, vanished wife, and actual age, must sigh and sighs and accept his fate; he reflects that he has, after all, been treated fairly enough. If his story has not attained the literary immortality that Cabell might have expected, at least it’s still occasionally read and enjoyed. Perhaps that too is a form of justice?

Matt Keeley reads too much and watches too many movies; he is helped in the former by his day job in the publishing industry. You can find him on Twitter at @mattkeeley.